-

The Tragic Life of Egon Schiele’s Secret Niece Revealed

Sarah Cascone, Artnet, April 17, 2025 -

A Secret Baby and a Nazi Hospital: The Untold Mystery Upending an Artist’s Legacy

Kelly Crow, The Wall Street Journal, March 23, 2025 -

Egon Schiele’s Art Draws New Audiences

Rebecca Schmid, The New York Times, March 2, 2025 -

New York's Kallir Institute Opens New Home

Hilarie Sheets, The Art Newspaper, November 1, 2024 -

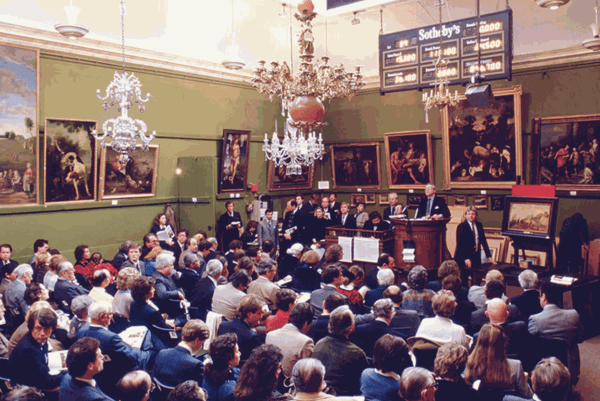

Shake It Up: Frieze Masters Galleries Blur Time Periods to Reflect a Shift in Market Demand

Kabir Jhala and Carlie Porterfield, The Art Newspaper, October 11, 2024 -

„kulturMontag“: Haags KHM-Abschied mit Rembrandt und van Hoogstraten, Schröders Albertina-Finale mit Chagall, #sogamoi in OÖ

Top News, October 4, 2024 -

How a Jewish Family and a Museum are Honoring an Artist Whose Work Remains Nothing Short of Devastating

Allan M. Jalon, Forward, July 15, 2024 -

“Becoming a fine art”: Walt Disney and The Art of Animation Exhibition, 1958–1966

Heather Lynn Holian, The Journal of American Culture, June 2, 2024 -

What Is the Future of the Digital Catalogue Raisonné? Experts Weigh In

Adam Schrader, Artnet, May 30, 2024 -

'Don't fear recession—it could create the art market’s next revolution'

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, April 14, 2023 -

I Visited New York’s Immersive Klimt Spectacular With One of the World’s Preeminent Gustav Klimt Experts. Here’s What Happened.

Ben Davis, Artnet, November 28, 2022 -

AI Digitally Restored a Lost Trio of Gustav Klimt Paintings. Not Everyone is Happy About It.

Ariana Aspuru, Wall Street Journal, October 22, 2022 -

AI, Art and the Future of Looking at a Painting

Ariana Aspuru (Producer), Wall Street Journal Podcast, August 19, 2022 -

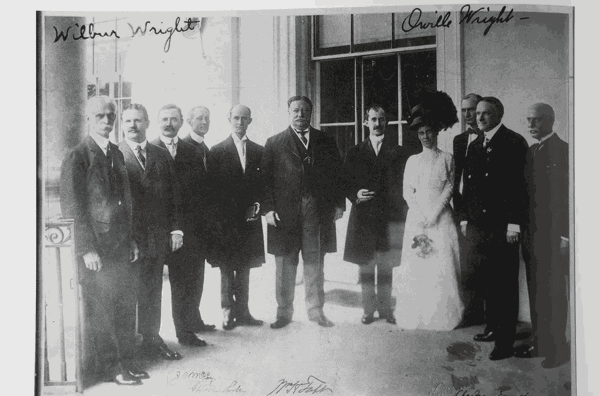

Time Collector Preserves Aviation History: A Serendipitous Discovery Uncovers Priceless Aeronautical Memorabilia

Peter Garrison, Flying Magazine, June 16, 2022 -

Are We Ready for the Philip Guston Exhibition at the MFA?

Jane Kallir, The Boston Globe, April 18, 2022 -

AI Digitally Restored a Lost Trio of Gustav Klimt Paintings

Jane Kallir, Wall Street Journal, November 12, 2021 -

Joining Plastic, Glass and Metal on the Recycle List: Fake Art

Experts say discredited works of art often resurface on the market again and again, in part because their owners just won’t take no for an answer.New York Times, October 14, 2021 -

Why Do Forgeries Sometimes Deceive Even the Most Venerable Experts? Because We All Want to Believe

Jane Kallir, Artnet, August 8, 2021 -

A Historic New York Gallery Is Turning Into a Nonprofit Research Institute Dedicated to Schiele, Grandma Moses, and Other Artists

Sarah Cascone, Artnet, March 10, 2021 -

What’s the ideal post-pandemic art market? One that's no longer a Disneyland for the rich

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, June 22, 2020 -

'We felt we had to make a choice and we chose scholarship': why Galerie St. Etienne went non-profit

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, November 22, 2019 -

Hildegard Bachert, 98, Dies; Championed Klimt, Schiele and Grandma Moses

New York Times, October 23, 2019 -

The Elephant in the Room: the Rise of Art-Related Lawsuits

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, May 21, 2019 -

Holocaust-Era Art Restitution: More Complex Than You Think

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, February 22, 2019 -

Art Authentication is Not an Exact Science

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, November 23, 2018 -

The All-Powerful Market is Sounding the Death Knell for Connoisseurship

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, October 9, 2018 -

Egon Schiele Was Not a Sex Offender

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, June 1, 2018 -

What is Art For? Jane Kallir Tells Us

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, December 13, 2015 -

75 Years With a Manhattan Gallery and No Sign of Stopping

New York Times, October 30, 2015 -

Comment: the problem with a collector-driven market

Jane Kallir, The Art Newspaper, July 1, 2007 -

It's Chic to Haggle for Art, Some Thrifty Collectors Find

Daniel Costello, Wall Street Journal, November 26, 1999